Crafting Community: Sustainability and Placemaking in Alberta’s Craft Beer Economy

Executive Summary

This integrative project explores the intersection of sustainability, community development, and placemaking within Alberta’s craft beer industry. Positioned against the backdrop of mass production and globalized economies, the study advocates for the value of craft economies as locally rooted, environmentally responsible, and socially enriching alternatives. Drawing from literature on craft traditions, the project highlights how artisanal methods—especially in food and drink—promote cultural heritage, reduce environmental impact, and strengthen regional identities. Although historically constrained by restrictive regulations, Alberta's craft beer scene has evolved into a hub for innovation and community-building. Breweries like Village Brewery and Mountain Tap exemplify how local sourcing, zero-waste practices, and community engagement align craft brewing with sustainable development. Craft brewers resist industrial norms by emphasizing manual skill, slow production, and ecological ethics and instead cultivate shared spaces, participatory governance, and economic resilience. This review underscores the potential of the craft economy not as a nostalgic return to the past but as a forward-thinking, place-based model for sustainable and inclusive development in Alberta and beyond.

Written by Callista Kruger

Introduction

The craft economy has emerged as an appealing alternative to dominant capitalist and mass production models. It offers pathways for more localized, sustainable, and community-centred modes of production. A key aspect of this shift is the role of craft in placemaking, which is the process of infusing physical spaces with meaning, identity, and a sense of belonging. This literature review explores how the craft economy, particularly in the craft beer industry in Alberta, promotes these dynamics through practices that emphasize quality, local sourcing, and community engagement instead of profit maximization. A growing body of literature highlights the potential of craft economies to create distinctive products while enriching cultural identity, supporting local livelihoods, and enhancing community resilience in the face of globalization and industrialization. By examining case studies and testimonials related to craft beer production, this review illustrates how the sector contributes to social cohesion, economic vitality, and environmental sustainability. The objective of this review is to synthesize current academic and empirical perspectives on the craft economy and its broader implications, emphasizing its importance as a viable model for community development and cultural preservation. Ultimately, it aims to provide a foundation for stakeholders, including policymakers, consumers, and artisans, to recognize and support craft-based industries.

What is Craft?

Before diving into the concept of craft itself, it is important to contextualize craft within the dominant economic system. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, craft was the dominant mode of production, closely tied to apprenticeships and manual skill (Mignosa & Kotipalli, 2019). However, the Industrial Revolution marginalized craft by introducing mechanized production and efficiency-driven approaches, resulting in the rise of mass production and standardized goods (Gold, 2009). In contemporary society, our economy is deeply entrenched in a capitalist framework that prioritizes efficiency and financial profit maximization. This has profound implications, as financial gain is often placed above critical considerations such as local economies and the sustainability of the environment. In this context, the heritage of craft faces challenges, struggling to find its place amongst the push for volume, speed and uniformity that defines modern manufacturing processes. Craft does not present a single, fixed definition; rather, the concept of craft is contested and varies by context (Mignosa & Kotipalli, 2019). Craft is not defined by materials or products, but a method of engagement that values manual skill and knowledge, context specific adaptation, collective governance and inclusion, as well as an emotional investment in both process and place. (Jones et al., 2021). It is both a product as well as a process that has roots in skill but also has been shaped by tensions between pre-industrial and modern modes of production and economies (Mignosa & Kotipalli, 2019). With consideration of our current economic state, it is important to consider the value of craft economies, as well as the threats and challenges that it faces.

Craft industries encompass a wide array of practices and are profoundly shaped by cultural traditions, economic frameworks, and policy environments. One of the most notable examples of such craft-making traditions can be found in the textile industries of countries like India and Indonesia. In these nations, textiles and weaving are not only vital sources of employment for many artisans but also carry rich cultural significance, often representing regional identities and historical narratives. Traditional methods of dyeing and weaving, passed down through generations, contribute to the uniqueness of their fabric designs, which are often characterized by intricate patterns and vibrant colours. Woodworking and furniture making are other essential categories in the craft industry, particularly in Japan. Here, the craftsmanship is revered, with skills honed over centuries that are prominently showcased in various applications, such as the construction of ancient temples and the creation of exquisitely detailed furniture. Japanese woodworking emphasizes precision, aesthetics, and a deep respect for natural materials, often incorporating techniques like joinery that require no nails, allowing for both strength and beauty in the final product. Ceramics and pottery also play a significant role in the craft landscape, tracing their origins to historical practices and evolving through movements such as the studio pottery movement in England and Wales. This movement emphasized the artist's hand and creativity, leading to a resurgence of handcrafted pottery that prioritizes both functionality and artistic expression. Modern artisans often draw inspiration from traditional techniques while innovating with form and glazing methods, resulting in pieces that reflect contemporary sensibilities yet maintain a connection to their heritage (Mignosa & Kotipalli, 2019).

Beyond these conventional craft areas, the definition of craft industries extends to include food and drink, which are, in many cultures, viewed as forms of artistry. Locally sourced, seasonal food preparation can be another example of craft where natural ingredients and low waste production are emphasized. For instance, artisanal baking is an esteemed tradition in France and Italy, where the techniques of bread-making, cheese production, and pastry crafting are deeply ingrained in the culinary landscape. Traditional techniques of fermentation and brewing are other common examples of craft food production, such as sake production in Japan or wine and beer production in Europe. These processes reflect local ingredients, historical practices, and regional variations, culminating in products that are not just sustenance but also embodiments of cultural pride and community identity (Mignosa & Kotipalli, 2019; Ratalewska, 2024). In this literature review, we will explore a case study of the craft beer brewing industry in the Alberta region to illustrate and contextualize the sustainability of craft production and how it can lead to placemaking and community building.

Craft and the Environment

Craftsmanship has long been revered not just for its aesthetic value but also for its significant environmental contributions. Craft is often contrasted with mass production and praised for being environmentally conscious by design, rather than a retrofit (Mignosa & Kotipalli, 2023). In an era where sustainability is paramount, the crafts sector stands out for its innovative practices aimed at reducing waste and promoting environmentally friendly production methods. One of the foremost contributions of craft is waste reduction. Many artisans adhere to the principle of zero-waste design, which emphasizes utilizing every part of a material rather than discarding it. This is often exemplified through the repurposing of broken materials, such as ceramic shards, which are creatively integrated into workshops and new creations. Such practices not only minimize waste but also inspire a culture of resourcefulness and creativity within the craft community. Upcycling is another vital aspect of modern craftsmanship. Artisans frequently transform what would otherwise be considered waste into art or functional products. For instance, textile remnants that may be deemed unusable in mainstream fashion are creatively repurposed into new garments or accessories (Mignosa & Kotipalli, 2023). This practice not only diverts materials from landfills but also encourages consumers to appreciate the potential of items that might typically be overlooked. Recyclability and reuse are further principles guiding the craft movement. Many artisans design their products to be durable and repairable, extending the lifecycle of their creations (Mignosa & Kotipalli, 2023; Ratalewska, 2024). This thoughtful approach contrasts with the throwaway culture prevalent in many industries today and encourages consumers to consider the longevity of their purchases.

Furthermore, the use of natural materials is a hallmark of many craftspeople. By selecting biodegradable, local, and non-toxic ingredients, artisans ensure that their products have minimal impact on the environment. This commitment to natural materials not only supports sustainable sourcing but also resonates with consumers increasingly seeking eco-friendly alternatives. Craft involves low-impact production techniques that distinguish it from large-scale industrial manufacturing (Ratalewska, 2024). Craft production is often inherently sustainable due to its reliance on traditional methods that have a low environmental impact and use locally sourced materials. In contrast to mass production, traditional crafts generate less pollution and waste, resulting in a lower carbon footprint. Craft emphasizes slow production over fast consumerism, thereby reducing overproduction and waste (Mignosa & Kotipalli, 2023). Many artisans rely on manual tools and small-batch systems, which significantly lessen energy consumption. This approach contrasts sharply with mass production, which is often energy-intensive and damaging to the environment. By favouring manual methods, craft makers can create products that are not only more sustainable but also imbued with a greater sense of authenticity and care. Lastly, knowledge-sharing among artisans plays a crucial role in promoting sustainable practices. Networks of craftspeople often facilitate the exchange of skills, techniques, and leftover supplies, fostering a collaborative environment. For example, studios and schools may share surplus materials, thereby further minimizing waste and encouraging the reuse of resources (Magdalena Ratalewska, 2024).

Craft and Placemaking

Craft industries have increasingly gained recognition for their contributions to sustainable economic development. Scholars highlight their potential to create jobs, support local economies, and preserve cultural knowledge (Mignosa & Kotipalli, 2020). Unlike mass production systems, which often rely on centralized capital, outsourcing, and automation, craft-based enterprises are typically small-scale, decentralized, and rooted in manual skills and cultural heritage. This structure makes them more resilient to global market fluctuations while providing stable long-term income opportunities for artisans. Moreover, craft economies align with ethical economic models that prioritize fairness and sustainability over profit maximization (Mignosa & Kotipalli, 2020). By utilizing local sourcing, slow production methods, and material reuse, craftspeople are able to reduce their environmental footprints while strengthening local supply chains. However, challenges remain; mass-produced imitations often undercut artisan-made goods in both price and visibility, making it difficult for traditional craft practitioners to compete. Scholars argue that consumer education is crucial for raising awareness about the authenticity, cultural value, and environmental benefits of handmade products (Ratalewska, 2024).

Beyond economic aspects, craft acts as a powerful tool for fostering social cohesion, local identity, and participatory governance. Although craft is often dismissed as outdated or anti-modern, it holds significant value in creating meaningful, place-based development strategies (Jones, Van Assche, & Parkins, 2020). Craft is not merely a remnant of tradition; it is adaptive, forward-thinking, and capable of coexisting with contemporary innovations and technologies. The relational and material aspects of craft are key to its ability to build community. Engaging directly with materials fosters a sense of care, intention, and local knowledge transfer. Craft production supports not only local livelihoods but also social well-being, cultural expression, and collaborative governance (Jones et al., 2020). These dynamics are particularly relevant in the context of urban regeneration, cultural placemaking, and local economic resilience.

Additionally, craft serves as a site for ecological and economic rethinking, especially within food systems. Drawing from degrowth theory, recent research has examined how craft food producers model sustainable, community-centered alternatives to the dominant growth-driven economy (Pacholok, 2023). These producers emphasize localism, reduced consumption, and ecological ethics, transforming food production into a form of resistance against extractive, globalized supply chains. In Alberta, examples of craft food systems include small-scale breweries, beekeeping operations, vegan cheese makers, and community farms, which apply degrowth principles in practice. These enterprises foster regional self-reliance, community education, and slow consumption, redefining consumers as co-producers and stewards of local economies (Pacholok, 2023). Furthermore, shared spaces such as farmers' markets and community kitchens act as hubs for skill-sharing, economic collaboration, and localized sustainability efforts.

Craft Brewing in Alberta

Unlike the thriving craft beer cultures that took root in British Columbia and Ontario during the 1980s and 1990s, Alberta’s journey into craft brewing has been slower, shaped less by community enthusiasm and more by legal red tape. While other provinces saw breweries multiply and flourish by the early 2000s, Alberta’s scene remained underdeveloped, not because people didn’t love good beer, but because the rules made it incredibly difficult to get started. Instead of growing organically from local demand, Alberta’s brewers had to navigate a tough regulatory landscape. Strict licensing laws required new breweries to prove they could produce enormous volumes of beer (up to half a million litres a year) before they could even open their doors. For many aspiring brewers, this made the dream financially out of reach.

Still, a few determined brewers forged ahead. In St. Albert, Hog’s Head Brewing made waves with bold, hop-heavy beers like the Hopslayer IPA, brewed on well-worn equipment salvaged from other breweries. In Edmonton, Yellowhead Brewery set out to become the city’s go-to lager, moving into a space that had once housed the now-defunct Maverick Brewing. And in Calgary, Village Brewery took a different approach altogether—building a brand around community, local arts, and cultural connection, under the slogan “It Takes a Village.” Each of these breweries carved out a place for themselves by blending creativity with grit, working under the weight of regulations that demanded high production capacity while trying to nurture local identity and community spirit (St. John, 2013).

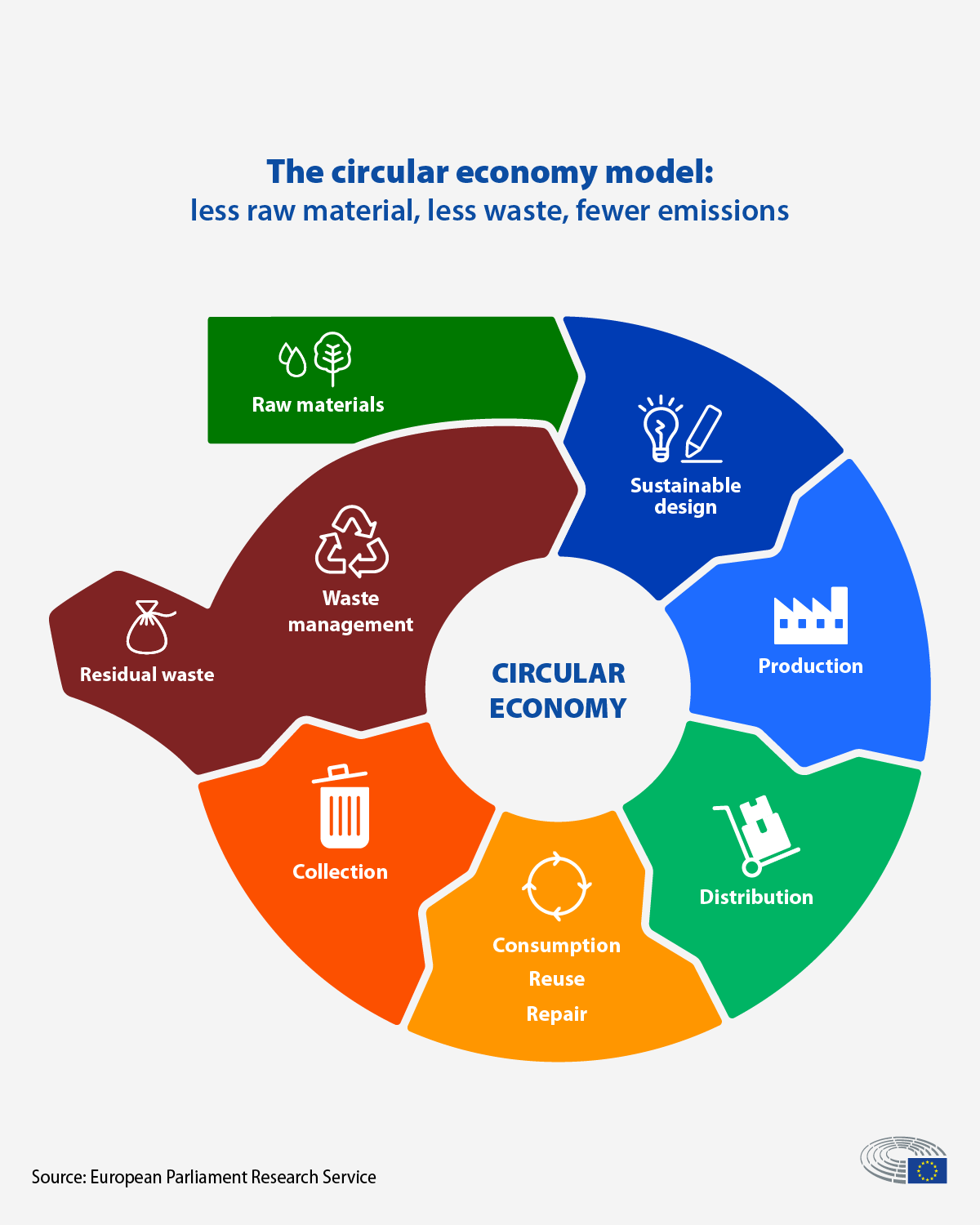

Craft brewing offers a compelling example of how small-scale, artisanal production can blend environmental care with economic and cultural sustainability. Unlike large industrial breweries that focus on efficiency, volume, and consistency, craft brewers tend to prioritize local roots, ecological responsibility, and meaningful community connections. In Alberta and beyond, craft breweries have embraced a slower, more intentional approach, one that supports resilient local economies while offering tangible alternatives to the impersonal nature of global supply chains (Pacholok, 2023). These breweries aren’t just talking about sustainability, they’re putting it into action. Many are adopting circular economy practices: recycling wastewater for cleaning or irrigation, turning spent grain into animal feed or even baked goods, and investing in renewable energy. For example, Mountain Tap Brewery has created a true “closed-loop” system, feeding their spent grain to pigs and later featuring that pork in their restaurant menu. Others, like Alice Springs Brewing Co., power most of their operations through solar panels, and Calgary’s Village Brewery has partnered with researchers to reuse treated municipal wastewater in the brewing process (Dingwall, 2021). At the heart of these efforts is a conscious rejection of the industrial mindset that values endless growth above all else. Craft brewers are choosing to stay small, rooted in their communities, and focused on quality over quantity. In Alberta, Village Brewery is a strong example of this approach—building its brand around storytelling, local art, and community initiatives, even as it navigated the challenges of restrictive provincial regulations (St. John, 2013). Together, these stories show how craft brewing can be more than just a business model. It becomes a cultural and environmental statement, a way to reimagine production not as a race to scale, but as an opportunity to connect people, protect the planet, and strengthen the places we call home.

Conclusion

This literature review has examined the multifaceted role of the craft economy, with a case study of Alberta’s craft beer industry, in promoting sustainability, community identity, and economic resilience. In an era where global systems emphasize scale, speed, and uniformity, the craft movement offers a meaningful alternative rooted in local knowledge, manual skills, and ecological ethics. Whether through zero-waste design, circular production, or place-based economic models, craft industries consistently show that viable alternatives to mass production are not only possible but already in progress. The environmental benefits of craft are particularly noteworthy. By utilizing natural, local materials, adopting low-impact production techniques, and fostering networks for sharing resources and skills, craft practices reduce waste and promote circularity. Additionally, craft plays a significant role in placemaking and preserving cultural continuity. It supports livelihoods while safeguarding community identity, enhancing social cohesion, and strengthening local governance structures. By emphasizing slowness, care, and intentionality, craft challenges the notion of infinite growth and redefines production as a space for participation, meaning, and resilience. This review illustrates that the craft economy is not a nostalgic return to the past but rather a forward-thinking model for building more just, sustainable, and grounded communities.

References

Blanco, C. A., Caballero, I., & Villacreces, S. (2022, February). Developments and characteristics of craft beer production processes. Food Bioscience Volume 45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbio.2021.101495

Dingwall, Kate. (2021). How Craft Brewers Are Embracing Sustainability. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/katedingwall/2021/03/14/how-craft-brewers-are-embracing-sustainability/

Gold, John R. (2009). City, Modern. International Encyclopedia of Human Geography (Second Edition). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-102295-5.10884-4

Jones, K. E., Van Assche, K., & Parkins, J. R. (2021). Reimagining Craft for Community Development. Local Environment, 26(7), 908–920. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2021.1939289

Mignosa, A., & Kotipalli, P. (Eds.). (2019). A Cultural Economic Analysis of Craft. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02164-1

Pacholok, T. I. (2023). Reimagining Craft as Alternate Sustainable Community Pathways: A Community-Based Participatory Exploration of Degrowth. [University of Alberta]. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat03710a&AN=alb.10457967&site=eds-live&scope=site

Ratalewska, Magdalena. (2024). Circular Economy in Creative Industries on the Example of Craft and Artisan Makers. European Research Studies Journal Volume XXVII Issue 3 1356-1372. https://doi.org/10.35808/ersj/3841

St. John, Jordan. (2013). Craft Brewing in Alberta – An Outsider’s Perspective. St John’s Wort. https://saintjohnswort.ca/craft-brewing-in-alberta/